Translate this page into:

Decreased Blood Flow in the Testis: Is it Testicular Torsion?

Corresponding Author: Allison Forrest, Department of Imaging Sciences, University of Rochester Medical Center, 601 Elmwood Ave, Box 214, Rochester, NY, 14642, United States. E-mail: allison_forrest@urmc.rochester.edu

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Forrest A, Brahmbhatt A, Dogra V. Decreased Blood Flow in the Testis: Is it Testicular Torsion? Am J Sonogr 2018, 1(13) 1-7.

Abstract

The absence of blood flow in the testis on ultrasound examination is the gold standard for diagnosis of testicular torsion. This imaging finding is seen in the vast majority of patients with testicular torsion, except in patients with partial torsion. Patients with partial testicular torsion may have reversal of arterial diastolic flow on spectral Doppler, decreased amplitude of the spectral Doppler waveform (parvus tardus wave), or monophasic waveforms. However, it is important to consider that not all absence of blood flow or reversal of diastolic flow in testis represents testicular torsion, as other conditions may have a similar appearance, including rare detection of such a pattern in normal asymptomatic patients. Conditions that commonly mimic testicular torsion include incarcerated inguinal hernias and complications following hernia repair,thrombotic phenomena, vasculitis, complicated epididymo-orchitis, asymptomatic variants, and technical limitations of ultrasonography. It is important for a practicing radiologist to be familiar with such cases to avoid unnecessary surgical interventions.We present a pictorial essay of cases in which the absence of testicular blood flow on color flow Doppler or abnormal waveforms on spectral Doppler are identified, without the presence of testicular torsion.

Keywords

Color flow doppler

Ischemia

Testis

Torsion

Ultrasound

INTRODUCTION

Scrotal pain is a common presenting complaint with a broad differential that ranges from acute diagnoses including testicular torsion, penetrating trauma, incarcerated inguinal hernia, and testicular rupture to non-acute diagnoses including epididymo-orchitis, appendicular torsion, and mild trauma. Genital or para genital infection is the most common cause of the acute scrotum, followed by testicular torsion and testicular trauma.[1]

Testicular torsion occurs when the spermatic cord and testicle twist around its axis, resulting first in venous obstruction, followed by decreased arterial flow and subsequent testicular ischemia. Testicular torsion is most common in younger men, though it can occur at any age, with a prevalence of 1 in 4000 in males younger than 25 years of age. It is associated with the bell-clapper deformity, a preexisting deformity in which the posterolateral aspect of the testes does not attach to the tunica vaginalis, allowing the testis to swing and rotate freely within the scrotum.[2] Partial torsion can also occur when the axis of the spermatic cord is rotated <360°, allowing a persistence of arterial inflow, in contrast to complete torsion (>360°), which impairs both arterial inflow and venous outflow.

Testicular torsion commonly presents with sudden onset of pain followed by nausea, vomiting, and absence of urinary symptoms. Physical examination shows a swollen and tender testis, an absent cremasteric reflex, and pain not relieved by elevation of the scrotum above the level of symphysis pubis.[2]

Testicular torsion must be identified and promptly manually or surgically reversed, as irreversible damage can begin as early as 6 h after the torsion event, with 50% of testes salvageable after 12 h, and 10% salvageable after 24 h.[2]

Doppler ultrasonography is the first-line imaging modality used to triage patients with acute scrotal pathologies.[1] When no detectable flow is seen in the testicle, the presumptive diagnosis of testicular torsion is made. Color flow Doppler alone has a sensitivity of 78.6%–89% and specificity of 77%–100% for the diagnosis of testicular torsion.[3] Power Doppler ultrasound is more sensitive in detecting blood flow and can improve the detection of flow with decreased velocities, though it may lead to false positives due to motion artifact.[4] Spectral ultrasound findings suggestive of testicular torsion include a monophasic waveform, increased resistance to arterial flow with a decrease in diastolic flow velocities and reversal of diastolic flow, or absence of arterial flow.[5] These findings are in contrast to the normal low-resistance, high-flow waveform of the testicular artery.[4] Spectral Doppler is also important in the diagnosis of partial torsion, which may demonstrate reversal of diastolic blood flow.[3]

Despite the high sensitivity and specificity of Doppler ultrasound in identification of testicular torsion, there are cases of the absence of blood flow and reversal of diastolic flow due to alternative conditions such as incarcerated inguinal hernias and complications following hernia repair, thrombotic phenomena, vasculitis, complicated epididymo-orchitis, asymptomatic variants, and technical limitations of ultrasonography.

The purpose of this pictorial essay is to present cases in which color flow and spectral Doppler ultrasound mimic testicular torsion to expand the radiologist’s differential diagnosis when presented with such cases.

ALTERNATIVE CAUSES OF DECREASED TESTICULAR FLOW

Extrinsic vascular compromise

Inguinal hernia and complications of inguinal hernia repair

Inguinal hernia can cause the absence of testicular flow, especially in the setting of an indirect hernia, which travels in the inguinal canal with the spermatic cord. The inguinal hernia, especially when incarcerated, triggers inflammatory processes and edema, resulting in the compression of the spermatic cord in the limited space of the inguinal canal. This creates a situation similar to closed compartment syndrome with resultant compression of the testicular artery, leading to testicular ischemia. This condition should be treated with prompt reduction of the hernia to avoid permanent ischemic damage to the testis (Figure 1).[6]

![A 58-year-old male with a known inguinal hernia presented to the emergency department with right-sided scrotal pain and swelling. (a) Color flow Doppler demonstrates a well-circumscribed loop of bowel with succusentricus with no evidence of blood flow. This hernia was non-reducible. (b) Power Doppler of the right testis demonstrates absence of complete blood flow in the right testis. Spectral Doppler demonstrates noise as evidenced by equal spectral amplitude above and below the baseline. (c) Status-post reduction, color flow Doppler examination demonstrates reactive hyperemia of right testis secondary to prior ischemia. (d) Status-post reduction, corresponding spectral Doppler confirms the presence of intratesticular blood flow. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [6].](/content/3/2018/1/1/img/AJS-1-13-g001.png)

- A 58-year-old male with a known inguinal hernia presented to the emergency department with right-sided scrotal pain and swelling. (a) Color flow Doppler demonstrates a well-circumscribed loop of bowel with succusentricus with no evidence of blood flow. This hernia was non-reducible. (b) Power Doppler of the right testis demonstrates absence of complete blood flow in the right testis. Spectral Doppler demonstrates noise as evidenced by equal spectral amplitude above and below the baseline. (c) Status-post reduction, color flow Doppler examination demonstrates reactive hyperemia of right testis secondary to prior ischemia. (d) Status-post reduction, corresponding spectral Doppler confirms the presence of intratesticular blood flow. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [6].

Inguinal hernia repair is most often an uncomplicated procedure but can result in injury to the vessels in the spermatic cord, resulting in testicular ischemia in 0.5% of cases.[7] Disruption of vessels can result in ischemia, with ultrasound examination showing hypoechoic parenchyma without detectable flow on color flow Doppler. Testicular volume may increase in the acute-subacute phase and decrease in the chronic phase.[8]

Careful surgical dissection is important in protecting the testicular vasculature during hernia repair. Minimizing disruption of venous outflow during repair can reduce the likelihood of thrombosis of the pampiniform plexus that could result in testicular venous infarction.[7] Inguinal hernia repair using mesh techniques may further increase the risk of testicular ischemia due to inflammation induced by the mesh itself, resulting in an acute scrotum.[9]

Sudden-onset hydrocele or hematoma

Hydrocele is a collection of fluid between the visceral and parietal layers of the tunica vaginalis that may form in the setting of abnormal fluid secretion, trauma, inflammation, or ischemia. In the setting of a sudden large hydrocele, the pressure of the fluid can exceed the pressure of the testicular vasculature, resulting in testicular ischemia and acute pain. These cases may be managed with prompt aspiration of hydrocele fluid or hydrocelectomy followed by repeat ultrasound to assess the return of blood flow or may be treated with testicular exploration and orchiopexy if suspicion for torsion is present (Figure 2).[10,11]

![A 61-year-old male with scrotal pain. (a) Longitudinal gray scale image of the scrotum reveals a large right-sided hydrocele deforming the testis into an elliptical form (b) Corresponding color flow Doppler of the right testis demonstrates a reversal of diastolic flow. (c) Sonogram of the right testis after hydrocelectomy shows reestablishment of normal intratesticular blood flow. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [5].](/content/3/2018/1/1/img/AJS-1-13-g002.png)

- A 61-year-old male with scrotal pain. (a) Longitudinal gray scale image of the scrotum reveals a large right-sided hydrocele deforming the testis into an elliptical form (b) Corresponding color flow Doppler of the right testis demonstrates a reversal of diastolic flow. (c) Sonogram of the right testis after hydrocelectomy shows reestablishment of normal intratesticular blood flow. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [5].

In our experience, we have also seen testicular ischemia after hydrocele repair, a rare complication of this procedure (Figure 3).

Hematocele can also result in compression of the ipsilateral testicular blood flow. This can occur following inguinal hernia repair due to damage to the pampiniform plexus.[12]

- A 57-year-old male with a large hydrocele. (a) Sagittal view demonstrates a large hydrocele with normal testicular blood flow. (b) Patient subsequently underwent hydrocelectomy. Patient presented 6 months later with no flow in the left testis on color flow Doppler, consistent with testicular infarction. (c) Similar findings are observed on power Doppler. This rare complication of testicular infarction after hydrocelectomy has not been reported before in literature.

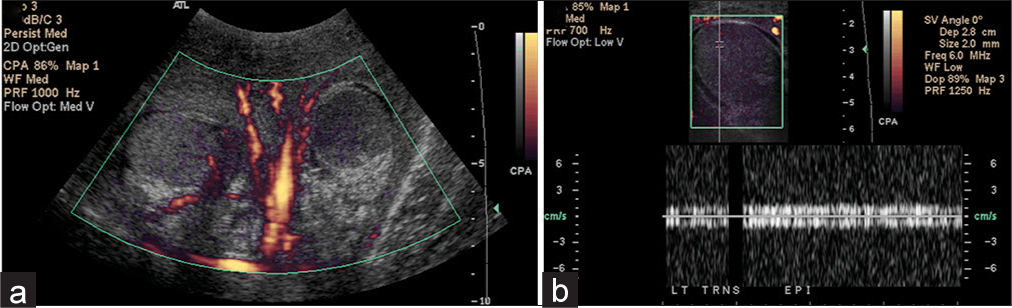

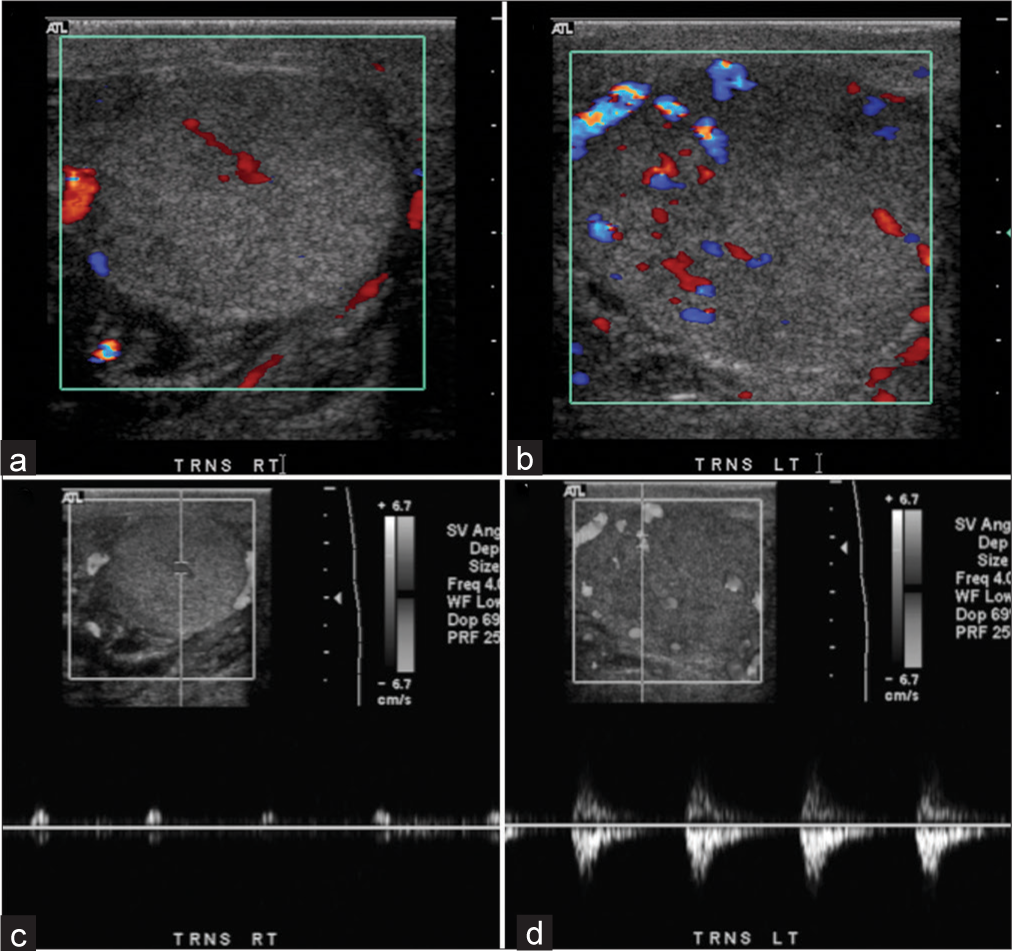

Other external compressions

In addition, external devices such as scrotal or penile rings can lead to compromised flow to the testes. Here, we demonstrate a patient with scrotal pain and edema after the use of a scrotal ring, resulting in the absence of blood flow to the testis (Figure 4). We also present a case of a patient with scrotal swelling due to a rubber band around his scrotum, found to have decreased blood flow and abnormal spectral waveforms (Figure 5). Several other examples have also been reported in the literature.[13]

- A 47-year-old male with a history of multiple sclerosis presented to the emergency room with penile and scrotal necrosis after wearing a penile pump and scrotal ring for 36 hours. (a) Power Doppler of both testes demonstrates flow in the right testis and absent blood flow in the left testis. (b) Corresponding image of the left testis demonstrates complete absence of testicular flow with noise on spectral Doppler. The patient was brought to the operating room for scrotal debridement and left orchiectomy.

- A 76-year-old male presented with a rubber band around his scrotum and scrotal swelling. (a) Transverse view of right testis demonstrates decreased blood flow on color Doppler. (b) Transverse view of left testis demonstrates near normal flow on color Doppler. (c) Abnormal spectral waveform with increased vascular resistance and no diastolic flow in the right testis. (d) Near normal spectral waveform in the left testis.

Intrinsic vascular compromise

Thrombotic/embolic phenomena

Protein S deficiency is associated with arterial and venous occlusion. This coagulation disorder has been implicated in case reports as a cause of global testicular infarction and may mimic testicular torsion due to the absence of Doppler color flow (Figure 6).[14] Similarly, antiphospholipid syndrome has been implicated in testicular ischemia due to an otherwise unprovoked thromboembolism.[15]

![An 84-year-old male presented with three days of worsening scrotal pain. Transverse sonogram of the testis shows a high-resistance arterial waveform with no diastolic flow, suggesting infarction. No venous flow could be detected. Patient was found to have a venous thrombosis and was discovered to be protein S deficient. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [5].](/content/3/2018/1/1/img/AJS-1-13-g006.png)

- An 84-year-old male presented with three days of worsening scrotal pain. Transverse sonogram of the testis shows a high-resistance arterial waveform with no diastolic flow, suggesting infarction. No venous flow could be detected. Patient was found to have a venous thrombosis and was discovered to be protein S deficient. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [5].

Cholesterol embolism post-endovascular aneurysm repair for the treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysm has also been reported and should be considered in patients with a history of recent vascular interventions.[16] This embolic phenomenon may also present as a focal infarct rather than total testicular ischemia, depending on embolic burden.

Sickle cell disease can also cause testicular infarction due to repeated vaso-occlusion by sickle cells.[17]

Vasculitides

Testicular vasculitis is rare, with most documented cases caused by polyarteritis nodosa. The testicular presentation of polyarteritis nodosa can occur either in isolation or along with other systemic manifestations. The resulting ischemia is often localized and demarcated. This is in contrast to the more diffuse ischemia seen in testicular torsion; however, diffuse ischemic involvement of the testis can occur in polyarteritis nodosa mimicking testicular torsion (Figure 7).

![A 35-year-old male presented to the emergency department with left scrotal pain. (a) Gray scale ultrasound demonstrates an enlarged, edematous left testis. (b) Color flow and spectral Doppler show no flow. (c) Corresponding histopathology (H&E, 200) demonstrates seminiferous tubules lined with viable (arrowhead) and nonviable (arrow) cells. Vasculitis can cause vasospasm, resulting in slow blood flow unable to be detected by ultrasound technology. Color flow Doppler ultrasound is unable to detect blood flow when the flow rate is less than 6 cm/second. As evidenced by histopathology, the testis was viable in this patient. However, due to inability of ultrasound to detect slow flow, this case was wrongly diagnosed as testicular torsion. Vasculitis or other causes of vasospasm should be considered in select cases. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [4].](/content/3/2018/1/1/img/AJS-1-13-g007.png)

- A 35-year-old male presented to the emergency department with left scrotal pain. (a) Gray scale ultrasound demonstrates an enlarged, edematous left testis. (b) Color flow and spectral Doppler show no flow. (c) Corresponding histopathology (H&E, 200) demonstrates seminiferous tubules lined with viable (arrowhead) and nonviable (arrow) cells. Vasculitis can cause vasospasm, resulting in slow blood flow unable to be detected by ultrasound technology. Color flow Doppler ultrasound is unable to detect blood flow when the flow rate is less than 6 cm/second. As evidenced by histopathology, the testis was viable in this patient. However, due to inability of ultrasound to detect slow flow, this case was wrongly diagnosed as testicular torsion. Vasculitis or other causes of vasospasm should be considered in select cases. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [4].

Other vasculitides that may involve the testes and result in the absence of testicular blood flow include vasculitis in systemic lupus erythematosus, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, giant cell arteritis, and Henoch-Schonlein purpura.[18,19]

Drug-mediated vasoconstriction

Case studies have shown that recent use of amphetamines, such as methamphetamine and cocaine, can lead to decreased testicular blood flow secondary to vasoconstriction through alpha-1 receptor activation.[20,21] These conditions should be considered in individuals with a history of recent substance abuse, as demonstrated in the case presented here (Figure 8).

![A 44-year-old male with a history of daily methamphetamine use presented to the emergency department with a 1-hour history of acute-onset right scrotal pain. (a) Color Doppler ultrasound of the right testis shows no detectable blood flow. (b) Spectral Doppler confirms the absence of flow. (c) Ultrasound of the right spermatic cord (arrows) shows no twist. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [20].](/content/3/2018/1/1/img/AJS-1-13-g008.png)

- A 44-year-old male with a history of daily methamphetamine use presented to the emergency department with a 1-hour history of acute-onset right scrotal pain. (a) Color Doppler ultrasound of the right testis shows no detectable blood flow. (b) Spectral Doppler confirms the absence of flow. (c) Ultrasound of the right spermatic cord (arrows) shows no twist. Reproduced with permission from Ref. [20].

Testicular pathology

Complicated epididymo-orchitis

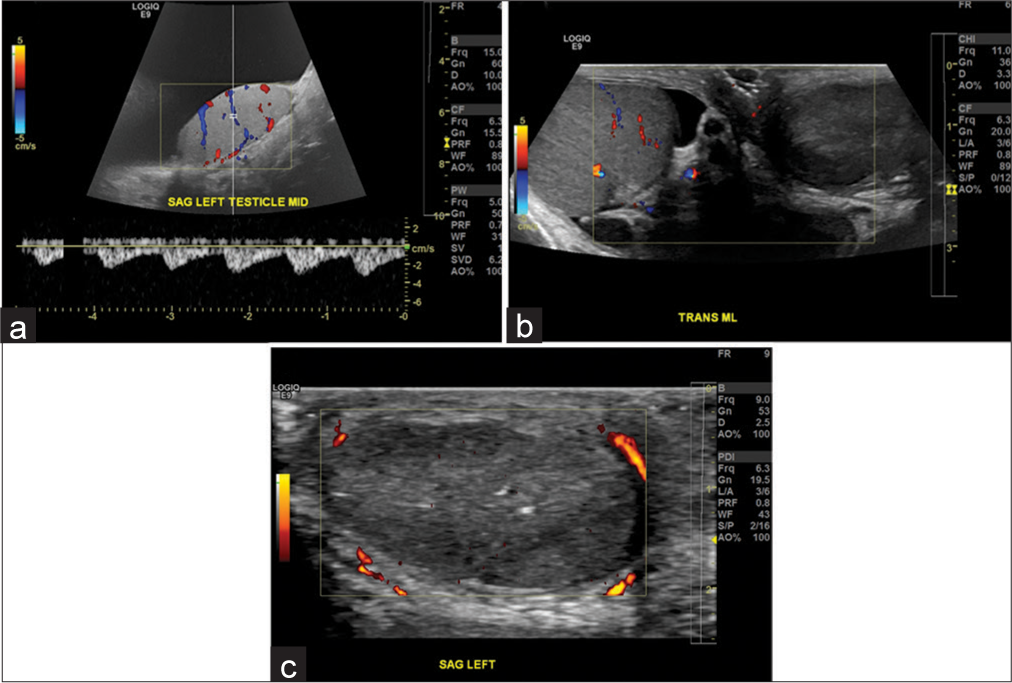

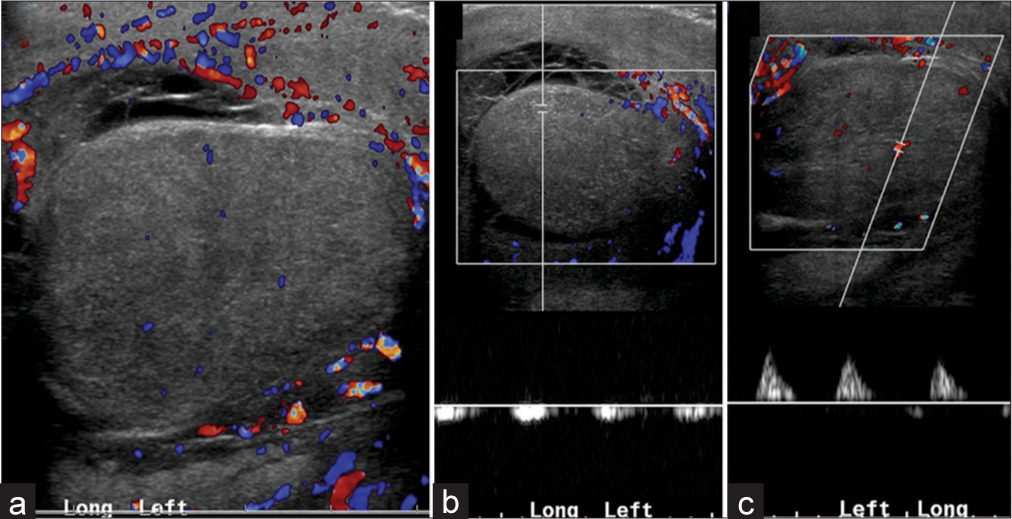

Complicated epididymo-orchitis may result in testicular infarction. Infection of the epididymis or testicle can result in marked swelling and edema of the spermatic cord that may impede testicular blood supply, in the absence of testicular torsion (Figure 9). In the setting of infarction complicating epididymo-orchitis, the affected testicle may develop ischemic orchitis, localized abscess, or diffuse gangrenous epididymo-orchitis.[22] Both testicular infarctions from orchitis and testicular torsion will show decreased echogenicity on ultrasound. These conditions must be differentiated with clinical and radiologic studies given that torsion requires orchiopexy due to a likely bilateral bell-clapper deformity, whereas severe epididymo-orchitis may require epididymotomy if severe.[22] If left untreated, complicated epididymo-orchitis can result in an atrophic and infarcted testis (Figure 10).

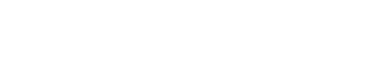

- A 22-year-old male with epididymo-orchitis on antibiotics. (a) Color flow Doppler demonstrates an enlarged, edematous testis with decreased blood flow. (b) Pardus tarvus waveform and (c) monophasic waveform in the same testis confirm high resistance to arterial inflow secondary to significant testicular edema.

![A 51-year-old male with epididymo-orchitis on antibiotics. (a) Spectral Doppler of the left testis shows reversal of diastolic flow indicating a high arterial resistance within the testis and has a pattern similar to that of partial testicular torsion. This pattern of reversal of diastolic flow in acute epididymo-orchitis suggests impending infarction. (b) 1 week later, spectral Doppler demonstrates increasing resistance to flow, as evidenced by decreased scale. Patient was lost to follow up and represented after 3 months. At that time, he was found to have an atrophic and dead left testis (not shown). Reproduced with permission from Ref. [5].](/content/3/2018/1/1/img/AJS-1-13-g010.png)

- A 51-year-old male with epididymo-orchitis on antibiotics. (a) Spectral Doppler of the left testis shows reversal of diastolic flow indicating a high arterial resistance within the testis and has a pattern similar to that of partial testicular torsion. This pattern of reversal of diastolic flow in acute epididymo-orchitis suggests impending infarction. (b) 1 week later, spectral Doppler demonstrates increasing resistance to flow, as evidenced by decreased scale. Patient was lost to follow up and represented after 3 months. At that time, he was found to have an atrophic and dead left testis (not shown). Reproduced with permission from Ref. [5].

Finally, funiculitis resulting from a filarial etiology has been implicated in testicular infarction. These infections should be considered in endemic regions.[23]

Other mimics

Asymptomatic variants

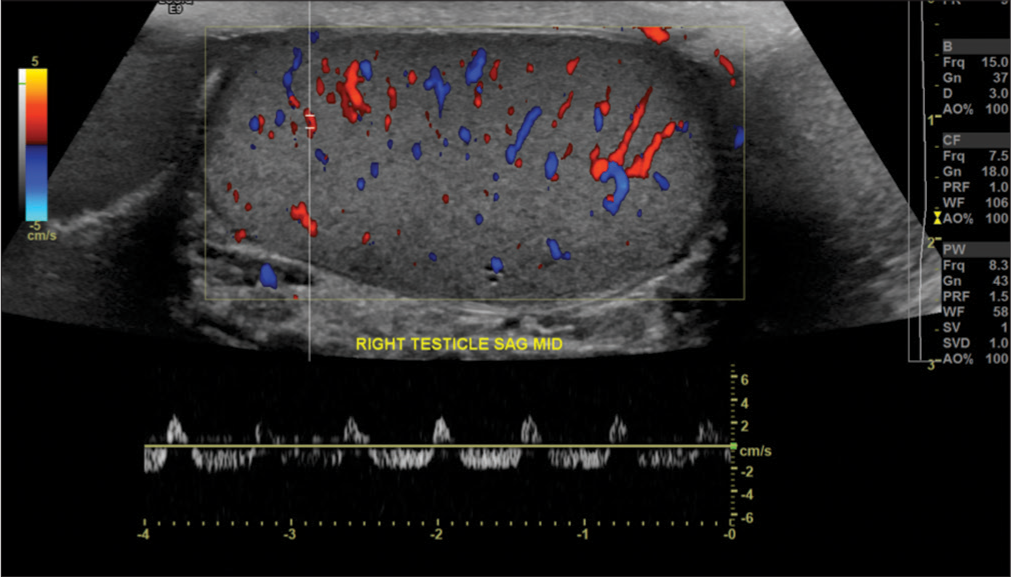

Variants in testicular blood flow and spectral waveform may also be identified without symptoms or need for intervention. Here, we demonstrate a patient with transient reversal of diastolic flow without clinical evidence of partial torsion (Figure 11). These findings underscore the important of clinical correlation in evaluation of testicular pathology, as the clinical presentation must guide diagnosis and management.

- A 44-year-old male with right scrotal pain, found to have varicocele. Ultrasound examination demonstrated reversal of diastolic flow on the right side. Upon repeat imaging, normal arterial waveforms were demonstrated throughout the testis, without reproduction of the reversal of diastolic flow (not shown). The patient was asymptomatic throughout. This reversal of diastolic flow may be observed in a patient without partial testicular torsion. However, persistence of this pattern should always raise suspicious for testicular torsion and this condition should be excluded.

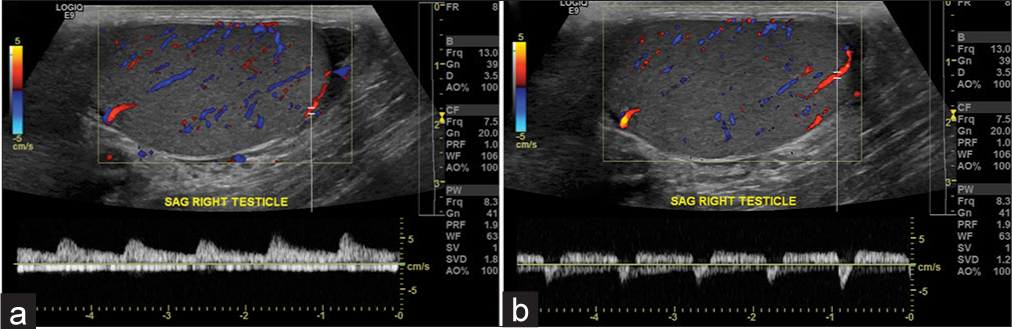

We also demonstrate a “to-and-fro” pattern due to a pseudoaneurysm in the right testicular artery, mimicking partial torsion (Figure 12).

- A 43-year-old male with right scrotal pain. (a) Normal waveform in the right testis. (b) Abnormal waveform in the lower pole of the same right testis, suggestive of “to-and-fro” pattern, which is commonly seen in the neck of a pseudoaneurysm. The sac of the pseudoaneurysm is not visualized in this study, likely secondary to the small size of the testicular arterial branch. This abnormal waveform most likely represents a congenital pseudoaneurysm of the testicular artery, as there was no history of trauma. However, most pseudoaneurysms of the testicular artery are traumatic or acquired.

Technical limitations of ultrasound

To best detect testicular blood flow, the ultrasound Doppler settings must be optimized for detection of slow flow, with adjustment for the lowest repetition frequency and the lowest possible threshold setting.[2] If the examination technique is not optimized, the absence of blood flow may be falsely identified.

The presence of thickened scrotal skin or large hydrocele may also decrease the sensitivity of the ultrasound examination and may falsely demonstrate monophasic waveforms suggestive of increased resistance to inflow.[4]

ADDITIONAL IMAGING MODALITIES

When diagnoses other than testicular torsion are being considered, alternative imaging modalities such as radionuclide scrotal imaging, computed tomography (CT), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be useful in evaluating for testicular torsion mimics. Historically, nuclear medicine scintigraphy was used for diagnosis of testicular torsion and can be used today as an adjunct to ultrasound. Scintigraphy in testicular torsion often shows a central photopenic area on static imaging, with a sensitivity of 90% and specificity of 89%.[24] Utilizing this imaging modality may be helpful in evaluating for testicular torsion in patients without demonstrable flow on ultrasound. MRI and CT may also be useful in further characterizing pathology, including inguinal hernias, vascular occlusion, thrombosis, and complicated epididymo-orchitis as possible causes of decreased blood flow or abnormal spectral Doppler waveforms. Further, dynamic contrast-enhanced subtraction MRI may be used to evaluate normal testicular perfusion and testicular pathology, including torsion and malignancy.[4] These imaging modalities can be used in selected populations without clinical evidence of testicular torsion to further evaluate for alternative causes of abnormal testicular ultrasound.

CONCLUSION

In this pictorial essay, we have demonstrated cases in which the absence of testicular blood flow on color flow Doppler or abnormal waveforms on spectral Doppler are identified, without the presence of testicular torsion. Practicing radiologists must be familiar with such cases to identify cases of testicular torsion mimics and avoid unnecessary surgical interventions.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Vikram Dogra is on the Editorial Board of the Journal.

References

- An accurate diagnostic pathway helps to correctly distinguish between the possible causes of acute scrotum. Oman Med J. 2018;33:55-60.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Role of spectral doppler sonography in the evaluation of partial testicular torsion. J Ultrasound Med. 2008;27:1629-38.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testicular torsion: Twists and turns. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2007;28:317-28.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torsion and beyond: New twists in spectral doppler evaluation of the scrotum. J Ultrasound Med. 2004;23:1077-85.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inguinal hernia resulting in testicular ischemia. Am J Sonogr. 2018;1:1-3.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Are there adverse effects of herniorrhaphy techniques on testicular perfusion? Evaluation by color doppler ultrasonography. Urol Int. 2005;75:167-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testicular ischemia after inguinal hernia repair. J Ultrasound. 2011;14:205-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testicular ischemia following mesh hernia repair and acute prostatitis. Indian J Urol. 2007;23:323-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tension hydrocele: An unusual cause of acute scrotal pain. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2015;31:584-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tension hydrocele: Additional cause of ischemia of the testis. J Ultrasound Med. 2012;31:2041-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testicular vascular flow compromise caused by compressive hematocele after lichtenstein hernioplasty. Hosp Physician. 1999;35:47-9.

- [Google Scholar]

- Scrotum incarceration with nine galvanized iron rings: An unusual case report. J Acute Med. 2016;6:95-7.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Testicular infarction secondary to protein S deficiency: A case report. BMC Urol. 2006;6:17.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patient with antiphospholipid syndrome presenting with testicular torsion-like symptoms. Urol Case Rep. 2017;15:26-7.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Acute global testicular infarction post-EVAR from cholesterol embolisation can be mistaken for torsion. EJVES Short Rep. 2017;35:11-5.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repeated testicular infarction in a patient with sickle cell disease: A possible mechanism for testicular failure. Urology. 2003;62:551.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- A case of scrotal swelling mimicking testicular torsion preceding henoch-schönlein vasculitis. Bratisl Lek Listy. 2012;113:382-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testicular vasculitis: A series of 19 cases. Urology. 2011;77:1043-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Methamphetamine use can mimic testicular torsion. J Clin Ultrasound. 2013;41:461-3.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cocaine abuse that presents with acute scrotal pain and mimics testicular torsion. Int Braz J Urol. 2016;42:1028-32.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Testicular infarction secondary to acute inflammatory disease: Demonstration by B-scan ultrasound. Radiology. 1984;152:785-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xanthogranulomatous funiculitis and orchiepididymitis: Report of 2 cases with immunohistochemical study and literature review. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:911-4.

- [Google Scholar]

- Diagnosis of acute testicular torsion using radionuclide scanning. J Urol. 1983;129:975-7.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]