Translate this page into:

Inguinal Hernia Resulting in Testicular Ischemia

Corresponding Author: Komal Chughtai, Department of Radiology, University of Rochester Medical Center, 1600 Elmwood Ave, Rochester, NY 14642, United States. E-mail: komal_chughtai@urmc.rochester.edu

-

Received: ,

Accepted: ,

How to cite this article: Chughtai K, Kallas J, Dogra VS. Inguinal Hernia Resulting in Testicular Ischemia. Am J Sonogr 2018, 1(3) 1-3.

Abstract

The absence of blood flow in the testicle is classically thought to be secondary to testicular torsion; however, other etiologies of compromised testicular blood flow have been described. We present an unusual case of testicular ischemia secondary to an inguinal hernia. A 58-year-old male presented to the emergency department with right-sided scrotal pain and swelling. Color-flow Doppler ultrasound evaluation demonstrated lack of blood flow in the right testicle and a right-sided inguinal hernia. The testicular blood flow was re-established with reduction of an inguinal hernia.

Keywords

Blood flow

Color-flow Doppler

Inguinal hernia

Testicular torsion

Testis

INTRODUCTION

Testicular torsion is the most common cause of loss of testicular blood flow. The other causes of absent testicular flow include technical limitations such as large hydroceles, significant scrotal wall edema, infection, and vasospasm.[1-6] In this report, we present the case of a 58-year-old male who presented with symptoms of testicular torsion but was found to have an inguinal hernia.

CASE REPORT

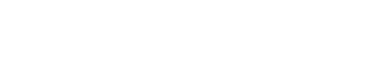

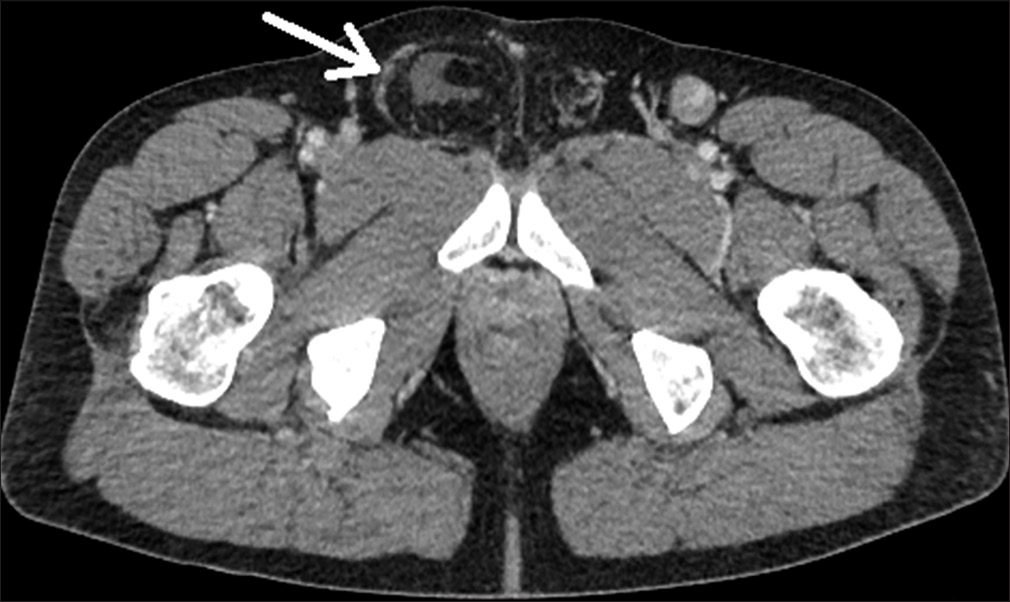

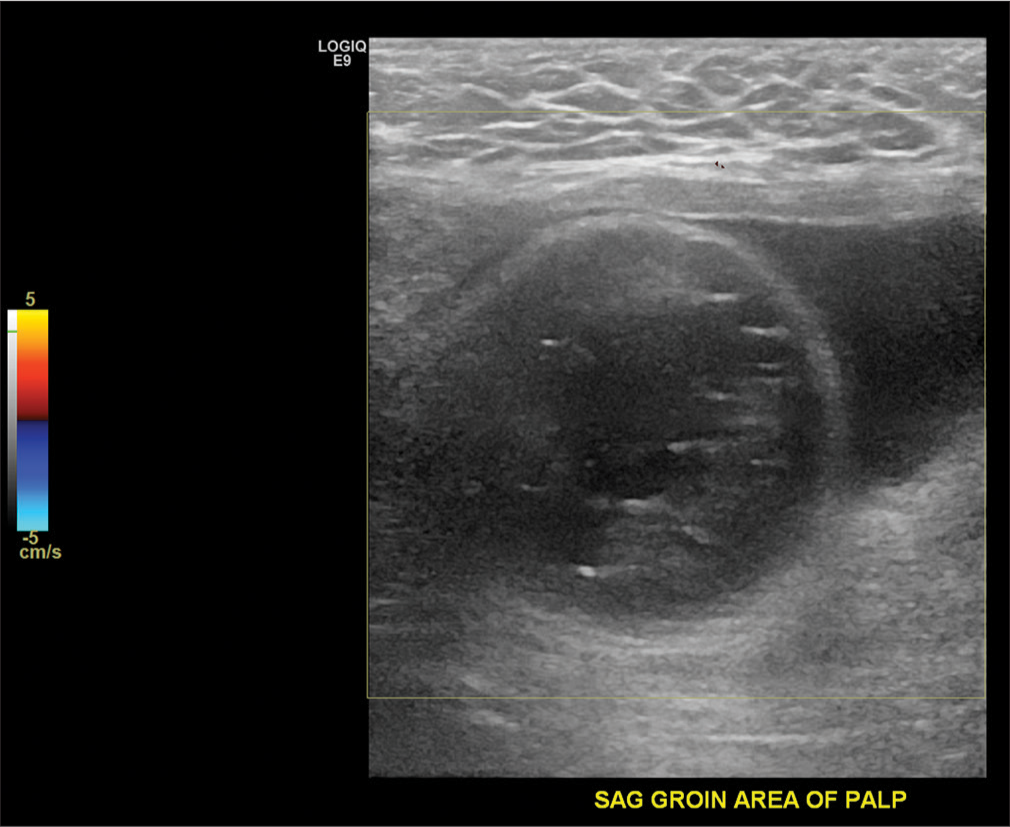

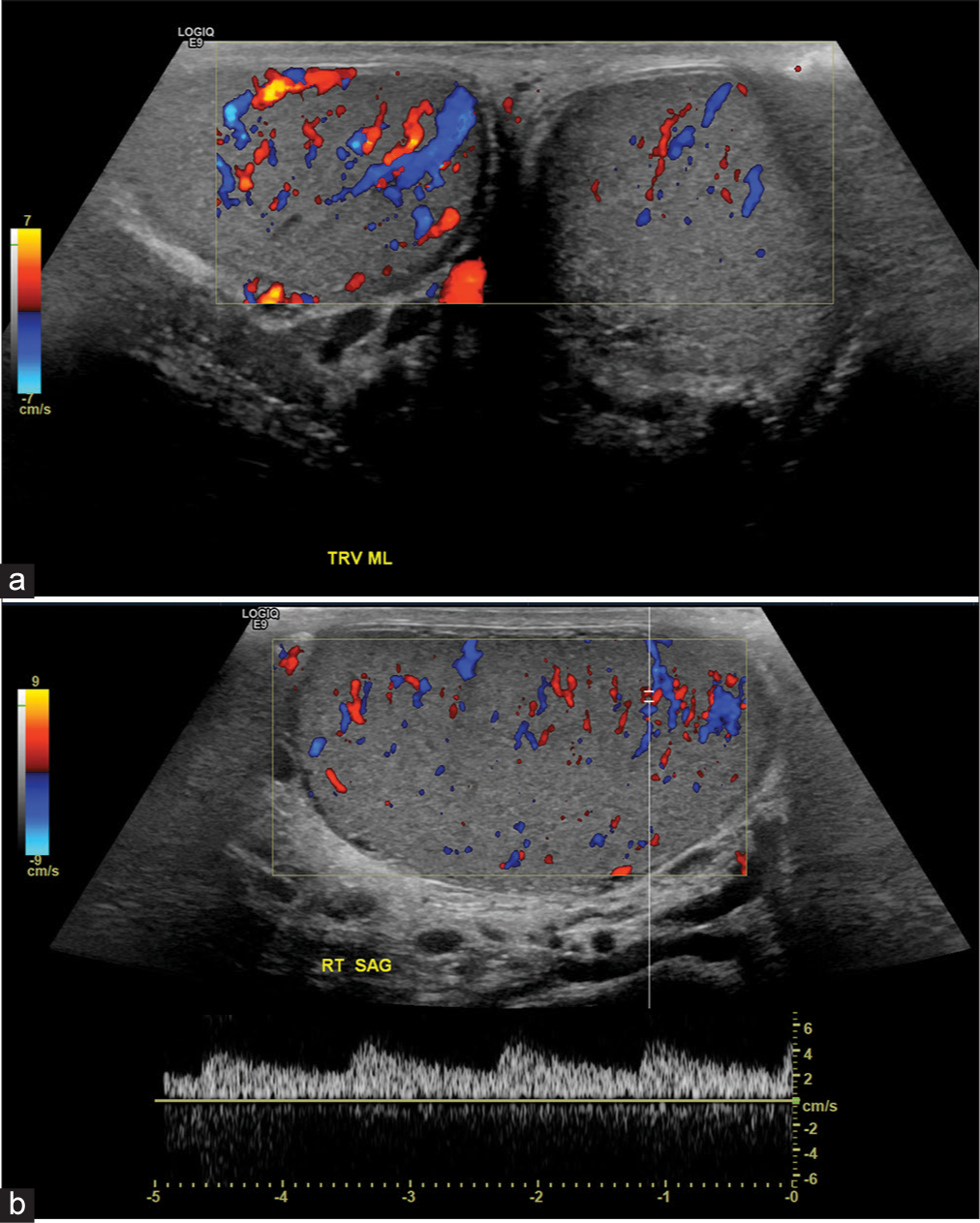

A 58-year-old male presented to the emergency department with increasing the right inguinal pain of gradual onset. The patient also felt a “bump” in the right inguinal region, presumed to be a known right fat-containing inguinal hernia, as diagnosed on a prior computed tomography abdomen and pelvis (Figure 1). Ultrasound examination of the scrotum and inguinal canal was performed using Logic E9 with liner 13 MHz transducer. Color-flow and power Doppler were also performed. These studies confirmed the presence of an irreducible right inguinal hernia (Figure 2). In addition, the right testis demonstrated decreased echogenicity compared to the left and complete absence of blood flow despite adjusting the gain and Doppler frequency for low flow state (Figure 3).

- A 58-year-old man presenting with abdominal pain. Computed tomography (CT) of the pelvis demonstrates a fat-containing right inguinal hernia (arrow) with accompanying minimal fluid. This study was performed ten days before the current presentation of the patient.

- A 58-year-old male presenting with right scrotal pain. Color-flow Doppler demonstrates a well-circumscribed loop of bowel with succusentricus with no evidence of blood flow (arrow). This hernia was non-reducible.

- A 58-year-old male presenting with right scrotal pain. (a) Color-flow Doppler image of the right testis in longitudinal view demonstrates decreased and complete absence of blood flow. echogenicity of the right testis secondary to ischemic event. (b) Power Doppler of the right testis demonstrates absence of complete blood flow in the right testis. Spectral Doppler demonstrates noise as evidenced by equal spectral amplitude above and below the baseline.

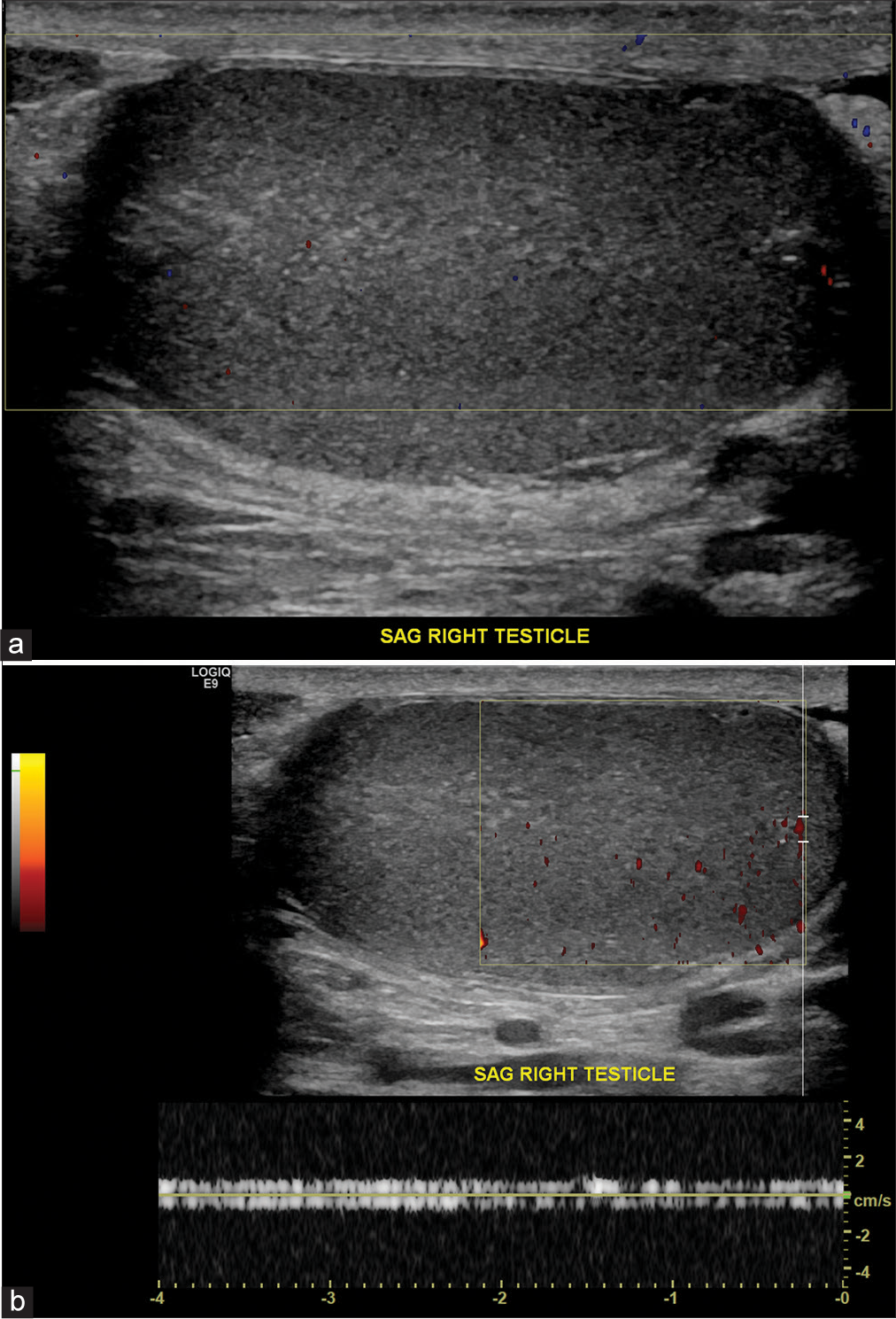

The patient was taken to the operating room emergently, and the inguinal hernia was reduced. Repeat ultrasound examination demonstrated the absence of right inguinal hernia and re-establishment of right testicular blood flow. Postoperatively, the right testis demonstrated increased intratesticular blood flow, compared to the left, secondary to ischemia-provoked reactive hyperemia (Figure 4).

-

A 58-year-old male presenting with right scrotal pain and right inguinal hernia, status-post reduction. (a) Color-flow Doppler examination demonstrates reactive hyperemia of right testis secondary to prior ischemia. (b) Corresponding spectral Doppler confirms the presence of intratesticular blood flow.

DISCUSSION

The incidence of testicular torsion in American males between ages of 1 and 25 years is 4.5 cases per 100,000 male subjects per year. Most of these patients are noted to have a Bell Clapper deformity. The Bell Clapper deformity is an abnormality in which the tunica vaginalis is attached high on the spermatic cord, leaving the testicle-free to rotate.[6] This predisposes the patient to testicular torsion. All patients with testicular torsion have Bell Clapper deformity; however, all patients with Bell Clapper deformity do not develop testicular torsion. Testicular torsion is defined as twisting of the spermatic cord by 360° or more. Complete absence of intratesticular blood flow is diagnostic of testicular torsion.[1,3,6] Partial testicular torsion is defined as a <360° rotation, in which arterial flow is present; however; there are increased inflow resistance and diastolic flow reversal.[3] Therefore, the presence of arterial blood flow does not exclude testicular torsion. Testicular torsion patients often present with abrupt onset of pain localized to the side of the torsed testicle.

The spermatic cord, comprising of testicular artery and pampiniform veins, travels through the inguinal canal which is a non-expandable compartment. An indirect inguinal hernia, when it occurs, also travels through the confined space of the inguinal canal alongside the spermatic cord. Consequently, it leads to compression of the testicular artery, leading to interruption of testicular perfusion. In addition, there is concurrent inflammatory response resulting in spermatic cord edema, further compromising the testicular artery. Once this hernia is reduced, the compression is relieved on the testicular artery resulting in testicular reperfusion. Given the imminent danger of testicular ischemia secondary to an inguinal hernia within the inguinal canal, timely evaluation of the testicle is imperative to prevent its ischemia. If found, an incarcerated inguinal must be emergently reduced to avoid the risk of testicular ischemic insult.

CONCLUSION

This case report illustrates the importance of evaluating the testicles in the presence of an inguinal hernia, given the risk of testicular ischemia. Inguinal hernia should be considered in the differential diagnosis of testicular ischemia to avoid unnecessary surgery and delay in diagnosis.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

Dr. Vikram Dogra is on the Editorial Board of the Journal.

References

- Testicular torsion: Twists and turns. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2007;28:317-28.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilateral testicular infarction caused by epididymitis. Am J Roentgenol. 1991;157:517-9.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Role of spectral doppler sonography in the evaluation of partial testicular torsion. J Ultrasound Med. 2008;27:1629-38.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inguinal hernia in infants: The fate of the testis following incarceration. J Ped Surg. 1984;19:44-6.

- [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Bilateral testicular infarction and orchiectomy as a complication of polyarteritis nodosa. Rev Urol. 2007;9:235-8.

- [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]